Jay Glazer vs. His F***edupness

The journalist and trainer's lifelong battle for healing — and love.

Warning: This story contains strong language.

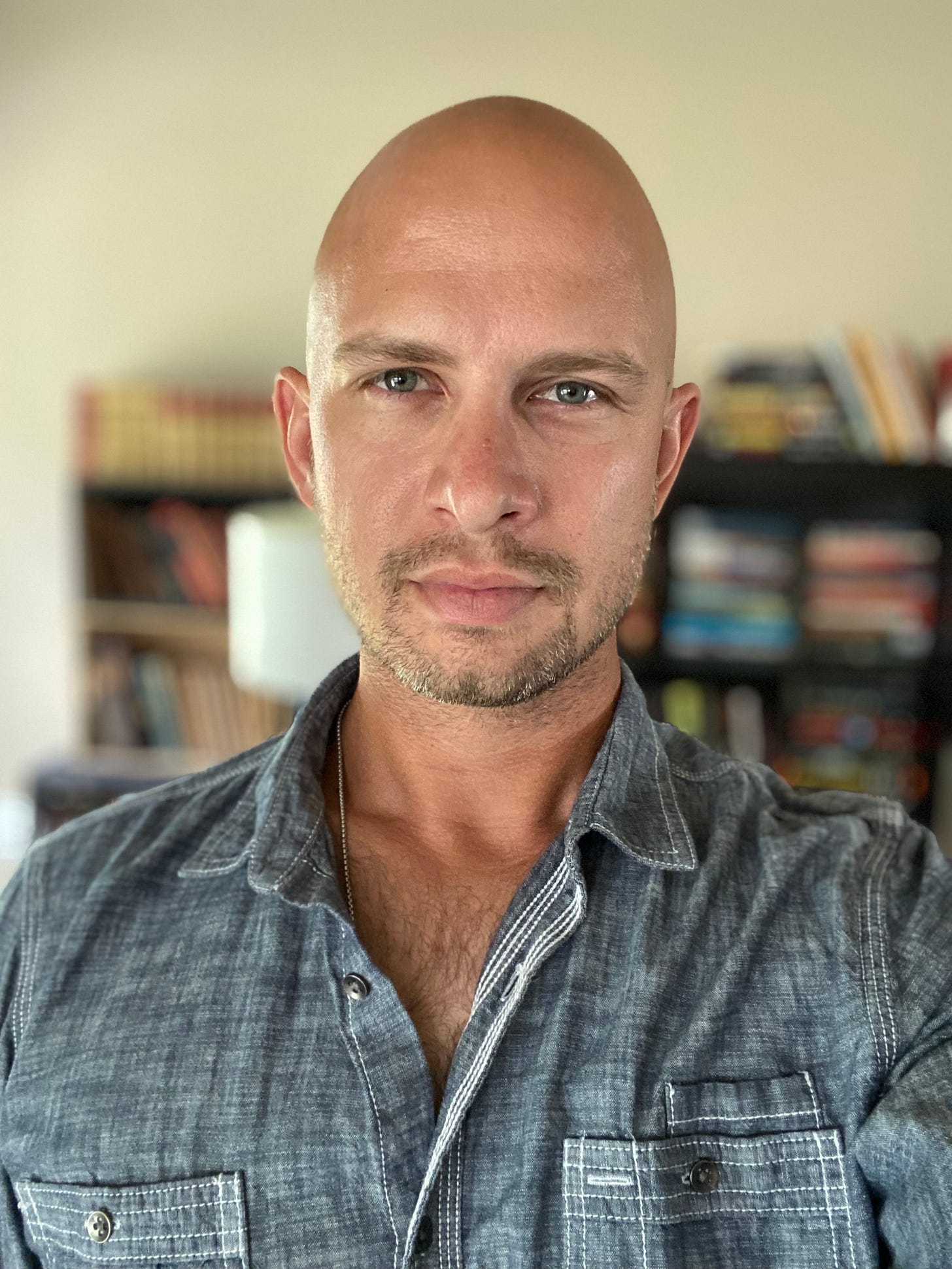

Sweat beads swell on Jay Glazer’s forehead and the crown of his bald scalp. He’s out of breath. His joints ache. The left side of his ribcage feels bruised. “I’m fucked up, man,” he says.

He looks and acts almost as if he’s just gone a few rounds with one of the UFC mixed-martial-arts champions he trains at his gym in West Hollywood. He’s wearing a dri-fit t-shirt and gym shorts — he just finished hiking — but he’s just sitting in the living room of his home in Malibu. “It’s not from the workout,” he says of his aches and pains. “It’s from the anxiety I woke up with this morning.”

He has been in a fight, one that exists within his head, which is exactly where he wants to keep it. “And sometimes,” Glazer says, “the beast gets out of the box.”

Some days, like today, he wakes up feeling all of it. Some call his affliction “demons.” The clinical terms are anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, PTSD, and ADHD. Recently, Glazer began calling it “The Gray.” For years, though, he just called it his “fuckedupness.”

And now, Glazer is telling the story of how not very long ago, “The Gray,” his “fuckedupness,” destroyed his relationship with the love of his life.

In many ways, by a certain age, all love stories are war stories. But Jay Glazer’s learning how to win that war.

Welcome to the Sneed Letter’s first Deep Dive, a narrative feature going deep on unforgettable people and moments at the intersection of sports, art, and culture.

I believe in great stories and want to grow this into an independent, sustainable outlet for great storytelling.

Read more about Sneed Letter here.

Subscribe below — or make a one-time contribution here — to support this work.

When I first met Glazer at his gym back in the fall of 2018, nobody knew about The Gray.

I only saw what the rest of the world saw: The Glaze, the persona that then-48-year-old Glazer had perfected over decades to make his way through life as the goateed bald guy built like a well-muscled whiskey barrel who kept everyone around him laughing or wanting to run through a wall — sometimes all at once.

Although Glazer had become famous for being one of the NFL’s top insiders, he loved mixed martial arts, too, and had trained in various forms of it for decades. His gym, Unbreakable, reflected his love for the craft. It includes not only a sprawling training area, but a full regulation octagon cage.

Many of his clients were among the world’s most accomplished performers in sports and entertainment, and Glazer was one of his clients’ primary trainers. For them, Glazer’s gym was a safe haven of sorts, a place where they get their ass kicked and do some ass-kicking of their own and feel good about it.

Glazer’s training, as physically rigorous as it was, was as much focused on mental health as physical health.

If Glazer felt his charges weren’t busting the appropriate amount of ass, he’d light into them. When one pop star you’d all recognize was slacking, he got into her face and told her that if she didn’t give her full effort, then how could she expect the same from others? In so many words, he asked her, Why should we keep giving to you if you don’t give back? Why should we lift you up if you won’t lift us up too? Give back as much as we give you! We need you!

She responded and proceeded to endure a thorough ass-kicking — and then she doled out her fair share of ass-kicking in return.

In other words: Glazer kicked people’s asses inside and out … and they loved it.

The first time we met, as busy as Glazer was, he was gracious and kind, taking time to talk off the record about one of the projects that had taken me to his gym in the first place, and then giving me his cell phone number so that we could talk later on the record.

He didn’t know anything about me other than that I’d told him I believed in good stories. If he could help, he was happy to talk.

I mention all of this to highlight that at this time in his life, Glazer only showed me what he showed everyone else: The Glaze. He didn’t let anybody else see the deeper darkness that existed behind that persona. Yet he was — in his own way — slowly trying to let those walls down.

“You want to see something really special?” Glazer asked me. “What really gets me going with all this shit? Come back Wednesday night. I’ll tell the guys to let you in.”

I went back Wednesday night.

The building that houses Unbreakable is built of pink stone, the former home of the Roxbury nightclub. On my first visit, across the road from the gym door on a small asphalt retaining wall, someone had graffitied a smiley face; the paint was fresh, some of the smile rolling straight down.

Inside, a group of athletes, entertainers, and military veterans gathered, talking and stretching. A blind veteran led by a service dog chatted with an amputee missing a leg. Glazer welcomed me and warned me not to record any conversations while I was there. Then he introduced me to Nate Boyer, a former Green Beret who went on to play football after his military service, first as a longsnapper for the University of Texas and then briefly for the Seattle Seahawks. Now an actor and activist, Boyer’s name may be familiar: during the 2016 NFL preseason, when Colin Kaepernick decided to sit in protest during the national anthem, Boyer suggested he kneel instead.

Prior to his brief stint with the Seahawks in 2015, Boyer trained at Unbreakable and became friends with Glazer. Along the way, he and Glazer decided to try to do something about the 22 military veterans who died from suicide every day. They developed a program they called MVP, for Merging Veterans and Players. Every Wednesday night, they welcomed veterans to Unbreakable free of charge and made sure that some of their friends from the worlds of sport and entertainment joined them.

The idea was simple: get everyone together to train and then deal with their shit, together. “They all get so isolated,” Glazer says. “Whether they’re military or former athletes or actors or singers, at some point, man, we all find ourselves feeling way too alone with our shit. This gets us together and makes us feel like part of a team we can count on, no matter what else happens in our lives and careers.”

That first night they started with a workout that included bodyweight exercises, mixed martial arts combat training drills, and more. Amputees and the blind helped each other. One woman’s service dog went through the drills with everyone. The physical work went on until everyone was drenched in sweat and exhausted. Then after the workout, Glazer gathered everyone around him and his featured guest, a famous actor who now was also sweating through his clothes, just like everyone else.

Together, they all held an informal group therapy session. Glazer started things off. He didn’t share many details, but he told everyone they were probably feeling fucked up in ways they didn’t think anyone else was, and to trust him, that they weren’t alone. “I’m fucked up, too,” he said. “But I’m good with my fuckedupness.”

That set the tone. The famous actor spoke next, sharing experiences from war movies he’d filmed and the one he was in training for now and the veterans he’d met throughout the process. He recognized that the only reason he got to play a soldier going to war was because all the veterans had really done it.

Then the soldiers spoke openly about the horrors of war and losing friends who had families and taking the lives of people who also had families. And then the agony of returning home from it all and trying to cope with the pain they carried back.

One veteran didn’t understand the point of talking about all the terrible shit that had happened, and said the only thing that helped him was kicking ass and, sometimes, just getting his ass kicked. Glazer calmed him and asked if anyone else cared to share another perspective. Another veteran said that therapy had saved his life because by talking about things, he came to understand them better, which helped him accept what he couldn’t change about his life.

In this way they all grappled together with their own personal fuckedupness. The details and experiences were all different, but each of them carried the same sort of pain. They’d sweat together, then they’d worked through their hells together. By the end of the night everyone in the room had cried at least once.

This happened every week. I attended another session later that year, this time in New York City as Glazer sought to expand MVP to other major cities. His endeavors were successful and soon the program took root in New York, Chicago, Las Vegas, and elsewhere.

Everywhere he went with it, Glazer used the same line: I’m fucked up, but I’m okay with my fuckedupness. The words resonated with me and, clearly, many others. But the thing is, Glazer never told anyone just how fucked up he really felt. He kept his mask on, the same one he showed me in 2018 — The Glaze.

Afterwards, sitting at home alone, usually after drinking too much wine or having too much Vicodin, Glazer says, “I was convinced I was the worst piece of garbage in the world.”

He’s one of the twenty percent of Americans — and one of roughly 29 million men nationwide — who suffer from mental illness every year. Like most, Glazer hid this fact about himself from everyone he knew for most of his life. He would do things like cancel dinner plans last minute, claiming an emergency or sudden illness. Not lying, exactly, but not quite the truth either. After trying more than 30 different medications, Glazer concluded that medication simply wouldn’t work; his body metabolized it too quickly. Therapy helped some, until it didn’t; most therapists weren’t quite sure what to do with him. One therapist got exasperated to the point of blurting out, “Jay, your life is great.”

To which Glazer, equally exasperated, responded, “Exactly! It’s between my ears that sucks!”

It all started when he was a kid. He grew up around people who were fighting wars of their own, and he became collateral damage, left with wounds that weren’t his fault. He’ll never tell those stories today because he still loves the people who gave him those wounds, but nevertheless, once he got the wounds, he was left to treat them on his own. At night while lying in bed, he’d just start talking to God. Nobody taught him how. “I’m not sure how I learned it,” he says. “It just made me feel less alone.”

As he grew up, to escape his pain, he threw himself into his training and his work, starting his sports journalism career working for pennies and living in a shitty little Manhattan apartment. Glazer sometimes had to beg for rides from players he covered, namely one “orthodontically challenged” New York Giants rookie named Michael Strahan. When they met, they were just two guys who didn’t know how they’d make it from where they were to where they wanted to go. In Glazer’s words, “We latched onto one another.”

Strahan, of course, went on to become one of the New York Giants’ all-time greats as a defensive end and a Hall of Famer. Glazer would become one of the sports world’s foremost insiders. But along the way, and for a long time after, Glazer struggled. He loved covering sports, but hated the way most reporters did it, manipulating and screwing over the athletes and coaches and organizations they covered. “I decided I would approach this job differently than everyone else,” he later said. “For example, instead of focusing on scoops, I would focus on the relationships … I built myself into the social structure of the locker rooms with those players.”

For a while, “the first fifteen or so years of using this approach,” Glazer said, “I got absolutely murdered by many of the other reporters, decimated for having these friendships.”

Glazer was accused of “using the players and not being objective.”

His perspective? “I felt they weren’t being objective by killing a player because he wouldn’t talk to them. Which is worse?”

Even that argument, however, missed the point: “What the reporters never fully grasped was, I wasn’t building these relationships solely for scoops,” he said. “I was building myself a team, a network who understood people like me and my fuckedupness. The players got it; the reporters really didn’t.”

In time, he became one of the most trusted journalists in football, breaking scoop after scoop — including one of the biggest in sports history when he got ahold of the tape that proved the New England Patriots’ Spygate cheating scandal — and making big money and living in sunny Southern California.

The sports world eventually knew him as a happy-go-lucky goateed bald guy who seemed to know everything about everyone in football. Soon, by way of appearances he made in various movies and television shows, figures in the entertainment world saw him in much the same way.

At the same time, other than his conversations with God, Glazer dealt with his pain alone. He primarily coped in two different ways. The first was to numb everything. Usually, that meant going home alone to drink and/or abuse Vicodin until he quit feeling anything.

He thought if people knew what was really going on with him, then he would somehow drag them down into the shit with him.

Or, more likely, if anyone knew how fucked-up he really felt, they’d abandon him, never wanting anything to do with him again.

“That,” Glazer says, “is just how it is with these mental health issues.”

The second way he found to cope was, in his words, “to be of service.” He threw any extra energy he had into charity work and helping people in any way he could. “When you are of service, it fights those voices back,” he says. “It gives you some relief. It gives you a thought to work with of, Well, maybe I’m not so bad.”

In 2013, a routine back surgery went wrong and nearly killed him.

During the procedure, unconscious under anesthesia, Glazer began vomiting, and then drowning in his vomit. The stomach acid began to destroy his lungs; he should have died. As he was dying on the table, he had an out-of-body experience in which he promised God that he would do more for people if he was allowed to live. And he lived. His doctors called it a miracle.

Glazer’s lungs were permanently damaged, and would never recover to their full capacity. The tube doctors put down his throat scarred his vocal chords, too, leaving his voice with its now-signature rasp. But Glazer followed through on his promise to God.

He was barely out of the hospital when he had friends take him — oxygen tank and all — to various locations in Los Angeles in search of a home for his gym, which he envisioned building as a safe haven for Los Angeles’ most driven, ambitious, and high-profile people. When he found the pink building on Sunset Boulevard, he knew that was it. Soon, Hollywood superstars, UFC heavyweight champions, billionaire businessmen — “the most badass kickers of ass in the world” — flocked to join him.

There, in that safe space, he could finally let his darkness loose a bit. He refused to speak openly about it to outsiders, but hinted at it, telling a reporter in 2015, “We are going to build you up, but in order to do this, we are going to take you to a dark fucking place, dude. We are going to take you to a dark place and come out the other side and you are going to be a different human being.”

Outwardly, he had everything a man could want: a lot of money, a great circle of friends, and an ever-increasing professional profile. He began regularly appearing on HBO’s Ballers, playing himself alongside one of his real-life best friends and star of the show, Dwayne Johnson.

But he still found himself waking up every morning feeling like the sky was falling. Glazer says he never felt suicidal, exactly, but he hated living this way.

“When you’re going through it,” he says, “you’re like, Man, why have I had so much pain? It’s really not fair.”

Still, he kept his full fuckedupness hidden from the world. The mask worked. Glazer was able to more or less keep its effects at bay when it came to his work and his friendships, but there was one place he couldn’t hide from it: when he was trying to love.

When COVID hit in early 2020 and the world went into lockdown, Glazer couldn’t just put MVP on pause. He adapted, switching to remote group workouts via Zoom, set up weekly with the help of his assistant, Nikki. One week, Nikki had a visitor, her friend Rosie Tenison. And over Zoom, while Nikki set up that week’s MVP session, Rosie and Jay hit it off.

A model and businesswoman who owned Varga, a small chain of fashion stores in the greater Los Angeles area, Tenison stayed on the Zoom call to watch Glazer lead the session. “And,” she says, “I just kept thinking, Wow — he’s so good at this.”

They stayed in touch afterwards, talking about life and work and God. As she learned about what Glazer was doing with MVP, she says, “It felt really important. And he was giving so much of his time and commitment, and he was helping so many people.”

She soon began to wonder: “He takes care of so many people — is there anyone really giving it back to him?”

For their first date, they went to the Santa Monica Pier, just down the street from Tenison’s apartment and one of her Varga shops. With the world in lockdown, everything was closed; it was just the two of them. They walked the pier and felt the salty wind and talked some more. “I just knew he was my soulmate,” Tenison says.

“I was just like, I want to be the one who takes care of him.”

For their second date, they were driving to Santa Barbara when Glazer’s phone started going off, with friends repeatedly asking if they were okay. Santa Monica was on fire — protests over the police killing of George Floyd had erupted into a riot. Glazer and Tenison raced back. By the time they reached her store, it was being destroyed. They went to her apartment, grabbed a few necessities, and skipped town.

Before long, they were in love — meaning that, right on schedule, Glazer’s fuckedupness began to take hold. A familiar pattern began to repeat: Time and again, he’d fall for someone who fell for him, only to destroy the relationship. “You sabotage,” he says. “You push people away … That was my pattern. I’m like, She’s gonna leave, because I’m not worthy of it. So you start making sure someone leaves, and you push them away. You pick little fights, or just kind of be down all the time … Nobody wants to stick around for that.”

Glazer and Tenison soon broke up. But for Glazer, this breakup felt different. “I was in a bad way,” he says. “She was my person. I couldn’t let her go. So I said, I gotta go make some dramatic changes. I gotta go really work on myself.”

He went to Kamalaya, a wellness resort located in Koh Samui, Thailand. It’s built around a storied cave which, according to legend, holds strong and mystical energy that deepens visitors’ connection to the universe. For centuries, Buddhist monks have inhabited the cave to further their spiritual practice.

“In other words,” Glazer says, “very much my shit.”

He entered the resort and made for the cave, where he met some monks. “First thing one of them says,” Glazer recalls, “is, ‘Man, you are in a lot of pain.’”

The monks instructed him to take a seat, and then they told him, “Sit with your pain.”

Glazer chuckled. “Man, I sit with my pain every day.”

“No,” a monk told him. “You experience your pain every day. We want you to really sit in your pain.”

“OK,” Glazer said. “How?”

A monk replied: “What did you call yourself growing up?”

“Jason,” Glazer said.

“Okay,” the monk said. “Sit in your pain, and hold little Jason’s hand. Show him compassion. He probably doesn’t feel like he’s ever had any. Go through that pain with him. Put your arm around him. Hug him. Just love him up. Let him know that it’s going to be okay.”

So he did. Glazer spent the rest of that day doing that, and then thirty days after that. Working with the monks, he uncovered the roots of his pain and worked through his grief. “I started healing this little kid me,” Glazer says. “Just taking care of little Jason. I learned to keep loving yourself up.”

One month can’t remove a lifetime of pain, but by the end of his time at Kamalaya, Glazer found what he needed to move through it. He called Tenison from Thailand. “Hey baby. I love you. And now I know how to be loved. I’m ready to be loved.”

From Thailand, Glazer flew to Arizona. “For my own mental health … I wanted to get out of Hollywood for a while,” he says. “It wasn’t a great place for that.”

Tenison met him there. They talked through their relationship, what Glazer had learned in Thailand, and what he wanted to keep learning from there. He found words to articulate his emotions and experience; it was while there he first came to call his fuckedupness “The Gray.” He decided to start being honest and open about his fuckedupness and began to develop plans to help others learn what he had learned. “One gift God and the universe has given me is communication,” he says. “So I’m just trying to find words that I can give to this experience that can help other people through it too.”

And in so doing, Glazer found an answer to that question that had long haunted him.

Why have I had so much pain?

“I realized, this is why,” Glazer says. “Maybe I’m in this kind of pain so that I can help others through theirs. If you can help one person, then it’s worth it.”

Upon his return to California, Glazer resolved to stop hiding his fuckedupness from people who cared about him. One night he had dinner plans with Strahan, but The Gray took hold, so Glazer called Strahan to cancel. And this time, for the first time in thirty years, he told the truth.

Strahan felt hurt. “I could’ve been there for you for thirty years,” he said. “And you took that away from me — the ability to be your best friend.”

Strahan’s warm embrace of Glazer’s struggle encouraged him to continue opening up to others about it. His colleagues from FOX received him in kind. “That’s the reaction that most people have had,” Glazer says. “It hasn’t been what I thought it would be — Oh, fuck, I don’t want to hear about that. Or, that’s too much. People want to be there for you.”

Network executives invited Glazer to give a talk to the entire company about what he’d endured and how he’d found a way through.

He wrote a book about it — also called, naturally, Unbreakable — and launched a podcast of the same name. As Dwayne Johnson wrote the foreword for Glazer’s book, he told him, “You’re going to be the voice for The Gray, for all of us.”

Glazer says, “I want to build one big, badass team together, so we could all get back together. That’s probably the biggest change for me. Now I feel like I have teammates.”

He still has his dark days. The difference now is in how he handles them. He does breathwork, he meditates, and writes lists of things he’s grateful for. “It’s really hard, when you’re in self-loathing, to be forcing yourself into gratitude,” he says.

Before bed, he meditates with a focus on the good in his day. “It’s like I’m coming home from a party,” he says. “And I used to dread waking up the next day. Because I always woke up to the sky falling. Now, this allows me to wake up excited for the day.”

Then there’s the one thing that helps him most of all, a beautiful irony for his life: the thing that used to be hardest for him has become his best tool. “Now, when I’m having a panic attack, I call people and just tell them I’m fucking struggling,” Glazer says. “And my people are the baddest dudes on the planet.”

He has people he’ll call simply to check on, too, without talking about himself at all. “That’s a pillar of mine: Being of service.”

One day, Glazer got an Instagram message from a man named Keith Madden:

Thank you for writing the book. It saved my life.

Glazer showed it to Johnson, who said, This is why you’re doing this, brother.

Then Johnson told him to ask Madden for his story.

A few DMs later, Glazer and Madden were on a call together.

Madden, a fifty-something contractor from Clemson, had been suffering similar to Glazer in various ways for years, and finally reached his personal breaking point. One day last year, he bought a bottle of tequila and drove to the beach. At the beach he planned to drink until the tequila was gone, and then walk out into the ocean. He would walk until the waves went over his head, and then he would swim and then the waves would take him.

“It was going to be that easy,” Madden tells me.

On the way, Madden stopped by Target. He saw Glazer’s book on a shelf and started reading it. For the first time in his life, he felt like someone understood him.

Madden still went to the beach but instead of going for that last swim, he kept reading.

“So,” he says, “I decided, I’m not doing it.”

This was a different sort of death, the kind where you realize you can live differently moving forward. After a few days, Madden drove home. He bought copies of the book to give out to friends. Read this, he told them. Trust me.

After Madden told Glazer that story, they stayed in touch. Now they text each other once or twice a week to check in on each other. How are you doing? How’s your week going? How are you feeling?

“You feel stupid when you tell somebody you just feel empty and hollow inside,” Madden says. “But you have to. You have to talk to people, and you have to check on them, too.”

Instead of The Gray, Glazer now realizes, “I was always wanting The Blue. And now existing in The Blue, I want to show everybody, we can live in The Blue. I’ve been there. I’ve been in The Gray, and I got out. And there’s a way out for us. As long as we do it together. I’ll never stop this journey now.”

Now that he’s learned how to heal, Glazer has a mission: “How do we weaponize it to help ourselves and help our lives and not be a victim anymore?” he says. “That’s the thing. I’ve been part of fight teams. And I want to build it.”

These days Glazer just lives out that mission: Keep helping people through their hurt, and in so doing, feel less of his own pain. “‘Hurt people hurt people,’ man. Right?” he says, echoing a famous quote. “Nothing helps me more than trying to help other people. And selfishly, I need that. I just don’t want to keep going around hurting people.”

True, I say, but at least so is the flip side of the quote.

“What’s that?” he says.

“Oh, you’ve probably heard it,” I say. “‘Healed people heal people.’”

He blinks and wipes at his eyes. “Fuck, man,” he says. “You’re gonna make me cry. Holy fuck. I’m gonna steal that for my next book.”

Maybe the most healing thing Glazer has experienced has been simply realizing how everyone who loves him — who really loves him — loves all of him, including the parts he calls his fuckedupness.

Now, instead of pushing Rosie away, he tells her: “Baby, the sky’s fallen again.”

She says exactly what he needs to hear: “Okay babe. I got you. I’m not going anywhere. I’m here with you.”

“No one else has ever convinced me that they’re not going anywhere,” Glazer says. “And I’d feel ashamed when I’d have my little meltdowns, but she forgets about it in two minutes. And she convinced me she doesn’t hold it against me. So I don’t sit in shame anymore like I used to. When you melt down you feel that shame and it lasts for a while. And she took that shame away from me.”

In March 2023, Glazer took Tenison to the Santa Monica Pier, back to the location of their first date. This time, the vendors were open, and the pier was full of people. They made their way through the crowd, to the end of the pier. Glazer knelt, reached in his pocket, pulled out a ring, and asked her to marry him. She said yes.

“I’m just so damn grateful, man,” Glazer says. “I’m fucked up, but I’m good with my fuckedupness.”

He pauses, having said his catchphrase for the millionth time in his life, but then says it again, with a twist I’ve never heard from him: “Actually, man, it’s more like — I’m learning how to be good with my fuckedupness.”

I’m Brandon Sneed, a writer based in North Carolina. I’ve written a few books and myriad feature stories for the New York Times, Rolling Stone, Sports Illustrated.

This is my newsletter, Sneed Letter. Too often, I come across amazing, emotional, vital stories that, for one reason or another, don’t neatly fit into mainstream media outlets. But I believe in great stories, period, and the otherworldly way they help us escape life’s pain.

To that end, I want to grow this into a respected and sustainable outlet for great, independent storytelling at the intersection of sports, art, and culture.

Support this work by following me on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter — and, most importantly, by subscribing to the newsletter and sharing this story.

You can also make a one-time contribution here.

Thank you for reading.